Masaccio's ‘Holy Trinity’ and the Birth of Perspective

In the history of Western art, few single works articulate the foundational spirit of the Renaissance with the potent economy of Masaccio’s Holy Trinity (c. 1425–1427). This seminal fresco, nestled within the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, is not merely a religious depiction, but a momentous synthesis. It is here that the imposition of classical architectural structure and geometric harmony confers a grandeur and solemnity fitting of the profound mysteries it contains: the finality of human death, the sacrifice of Our Lord, and the sublime truth of the Holy Trinity. This masterpiece serves as the Renaissance's rational argument for the divine, translating eternal truths into a comprehensible, ordered visual language.

To fully grasp the preeminence of Masaccio's Holy Trinity, one must view it within the context of Santa Maria Novella, a basilica that serves as a chronological textbook of Florentine art. In the center of the nave, high above, hangs Giotto’s Crucifix (c. 1290). This earlier work is a masterpiece of the Proto-Renaissance, moving away from Byzantine abstraction to give Christ’s figure genuine human weight and emotional sorrow (Christus Patiens). Later, in the transept, are the expansive narrative cycles, such as those in the Tornabuoni Chapel (by Ghirlandaio) and the Strozzi Chapel (by Filippino Lippi), which fully embrace Renaissance space but use it primarily for elaborate storytelling and the celebration of patron wealth.

To fully grasp the preeminence of Masaccio's Holy Trinity, one must view it within the context of Santa Maria Novella, a basilica that serves as a chronological textbook of Florentine art. In the center of the nave, high above, hangs Giotto’s Crucifix (c. 1290). This earlier work is a masterpiece of the Proto-Renaissance, moving away from Byzantine abstraction to give Christ’s figure genuine human weight and emotional sorrow (Christus Patiens). Later, in the transept, are the expansive narrative cycles, such as those in the Tornabuoni Chapel (by Ghirlandaio) and the Strozzi Chapel (by Filippino Lippi), which fully embrace Renaissance space but use it primarily for elaborate storytelling and the celebration of patron wealth.

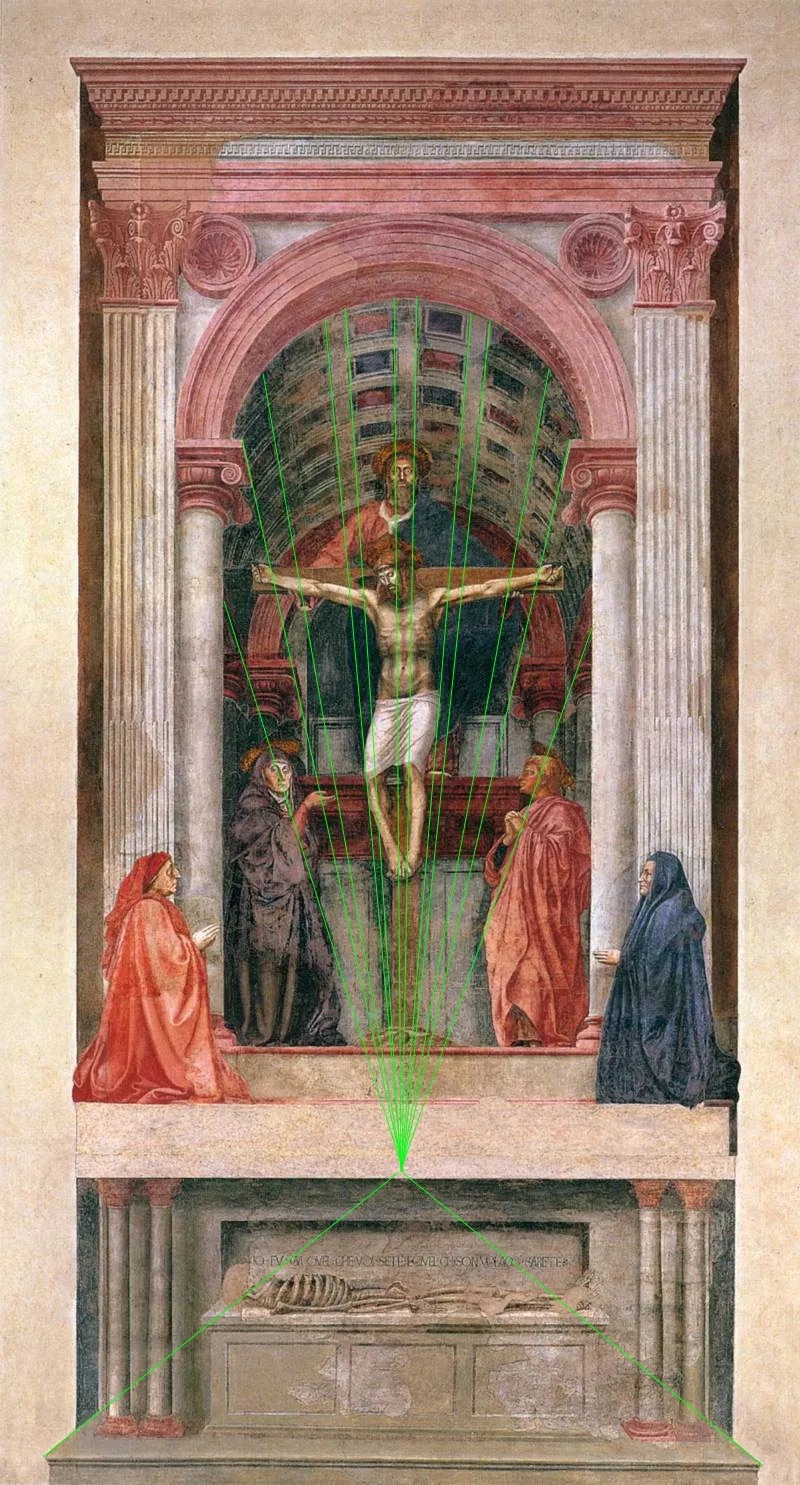

Masaccio’s fresco, located on a side wall in the third bay of the left aisle, is often overlooked as a central altar but is, in fact, the founding document of the Renaissance within the entire church. Its historical primacy lies in its radical demonstration of linear perspective, using the mathematical theories of Filippo Brunelleschi. While Giotto achieved emotional truth, Masaccio achieved rational, scientific truth. This revolutionary act of turning a flat wall into a measurable, deep classical chapel, rather than just decorating it, elevates the Holy Trinity beyond all other works to become the most intellectually and technically impressive piece in the basilica, regardless of its off-center location. It declared that human intellect and classical ratio were the new, most potent tools for comprehending and conveying the divine.

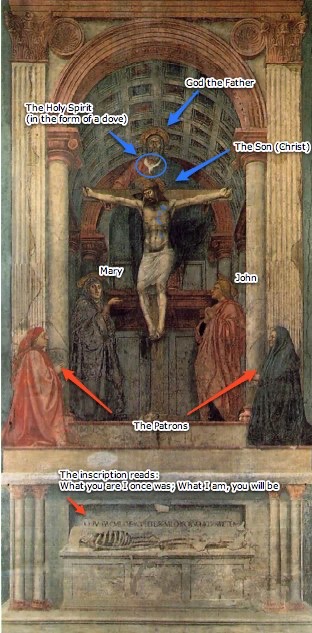

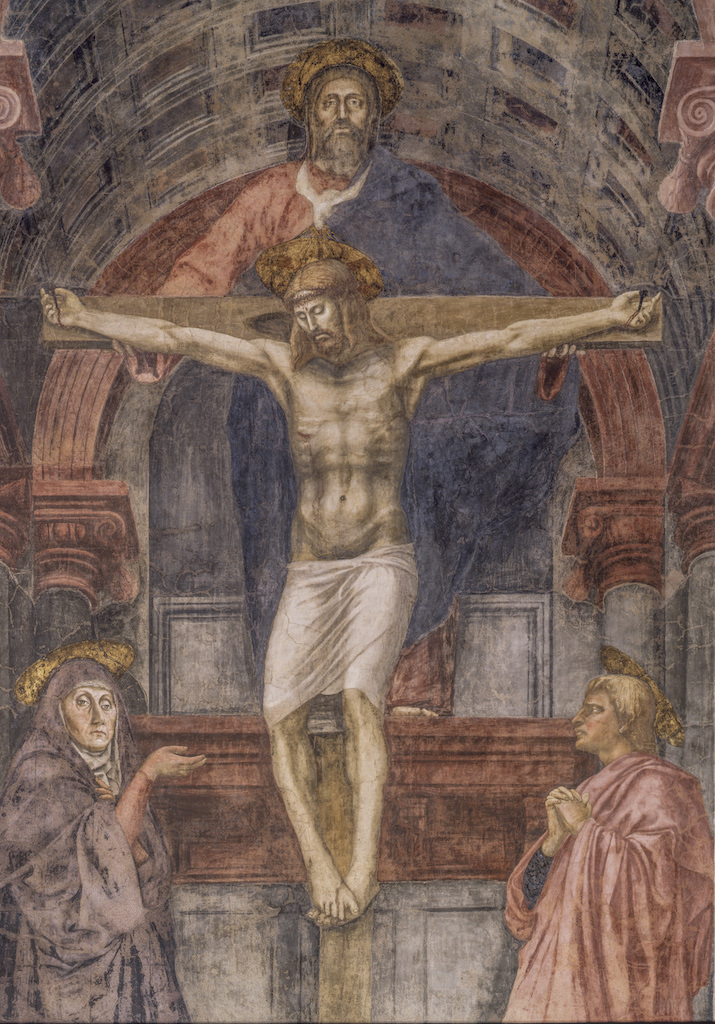

The work’s profound aesthetic impact stems from this revolutionary and fastidious application of nascent classical principles. Masaccio constructs a powerful trompe-l'œil chapel—a rigorous, logical framework built around a single vanishing point. This architecture itself embodies a quintessential metric of classical beauty: harmonious proportion and balanced order. The coffered barrel vault, supported by Ionic columns and flanked by Corinthian pilasters, is a direct, reverent quotation of Roman antiquity. The measured rhythm of these classical forms functions as the structural and spiritual apogee of the composition, containing and elevating the Trinity. The choice of such ordered, permanent architecture elevates the divine scene, providing a sense of solemn, eternal fitness for the central mystery of the faith.

The work’s profound aesthetic impact stems from this revolutionary and fastidious application of nascent classical principles. Masaccio constructs a powerful trompe-l'œil chapel—a rigorous, logical framework built around a single vanishing point. This architecture itself embodies a quintessential metric of classical beauty: harmonious proportion and balanced order. The coffered barrel vault, supported by Ionic columns and flanked by Corinthian pilasters, is a direct, reverent quotation of Roman antiquity. The measured rhythm of these classical forms functions as the structural and spiritual apogee of the composition, containing and elevating the Trinity. The choice of such ordered, permanent architecture elevates the divine scene, providing a sense of solemn, eternal fitness for the central mystery of the faith.

The six figures in the composition are meticulously placed and dressed to articulate the spiritual and social hierarchy of Christian devotion, further emphasizing the scene’s solemnity. The Trinity (Father, Son, Holy Spirit) occupy the deepest, most sacred space under the architectural vault. Our Lady and St. John the Apostle stand upright at the foot of the cross, closer to the viewer, their vertical posture affirming their status as saints and intercessors despite their conveyed reverence and grief. Finally, the Devout Donors (likely the Lenzi family) kneel just outside the sacred archway. Clad in contemporary Florentine fashion and placed at the viewer's eye level, their humble, kneeling posture is profoundly significant. It visually separates them from the standing holy figures and models the correct devotional attitude for the faithful: humility at the precipice of the divine mystery.

The most compelling aspect of the fresco’s lower tier is the memento mori (reminder of death), a skeleton lying on a sarcophagus . This painted tomb was placed directly above the real-life burial site (the family crypt) of the patron family in the church floor. Above the skeleton is the epithet: "I once was what you are, and what I am you will become." This short phrase carries a profound dual significance. If taken as being spoken by the skeleton, the meaning is a straightforward warning: you, the living, will inevitably become dry bones like me. However, if the final phrase, "what I am you will become," is taken as a promise from Christ on the cross just above, the meaning shifts entirely. The faithful are invited to believe that by living a devout life and accepting Christ’s sacrifice, they will ultimately achieve deification (theosis), becoming like Christ in heaven—a powerful and complex promise of transfiguration. By aligning the viewer's inevitable death (the skeleton) with Christ's redemptive sacrifice, Masaccio frames salvation not as an abstract miracle, but as the merciful answer to the physical certainty of the grave, beautifully contained by the rational structure of his architectural vision.

The most compelling aspect of the fresco’s lower tier is the memento mori (reminder of death), a skeleton lying on a sarcophagus . This painted tomb was placed directly above the real-life burial site (the family crypt) of the patron family in the church floor. Above the skeleton is the epithet: "I once was what you are, and what I am you will become." This short phrase carries a profound dual significance. If taken as being spoken by the skeleton, the meaning is a straightforward warning: you, the living, will inevitably become dry bones like me. However, if the final phrase, "what I am you will become," is taken as a promise from Christ on the cross just above, the meaning shifts entirely. The faithful are invited to believe that by living a devout life and accepting Christ’s sacrifice, they will ultimately achieve deification (theosis), becoming like Christ in heaven—a powerful and complex promise of transfiguration. By aligning the viewer's inevitable death (the skeleton) with Christ's redemptive sacrifice, Masaccio frames salvation not as an abstract miracle, but as the merciful answer to the physical certainty of the grave, beautifully contained by the rational structure of his architectural vision.

Masaccio’s Holy Trinity is thus far more than a devotional image; it is an epochal statement forged in fresco. Its historical primacy lies not in its physical location—a humble side wall rather than the central altar—but in its intellectual ambition. By imposing the flawless classical ratio of perspective onto the Christian narrative, Masaccio achieved a grandeur and solidity unrivaled by other great works within Santa Maria Novella, including Giotto’s earlier, emotionally intense Crucifix. The fresco serves as the manifesto of the Early Renaissance, declaring that the ordered, rational human mind, rediscovered through classical study, was perfectly capable of imagining and honoring the deepest mysteries of the faith. By unifying the architectural rigor of the coffered vault with the complex theology of the dual epithet—simultaneously promising physical decay and spiritual deification—Masaccio provided the Florentine faithful with a comprehensive visual charter: a beautifully ordered path from the physical reality of the family crypt to the eternal promise of the Holy Trinity.

Masaccio’s Holy Trinity is thus far more than a devotional image; it is an epochal statement forged in fresco. Its historical primacy lies not in its physical location—a humble side wall rather than the central altar—but in its intellectual ambition. By imposing the flawless classical ratio of perspective onto the Christian narrative, Masaccio achieved a grandeur and solidity unrivaled by other great works within Santa Maria Novella, including Giotto’s earlier, emotionally intense Crucifix. The fresco serves as the manifesto of the Early Renaissance, declaring that the ordered, rational human mind, rediscovered through classical study, was perfectly capable of imagining and honoring the deepest mysteries of the faith. By unifying the architectural rigor of the coffered vault with the complex theology of the dual epithet—simultaneously promising physical decay and spiritual deification—Masaccio provided the Florentine faithful with a comprehensive visual charter: a beautifully ordered path from the physical reality of the family crypt to the eternal promise of the Holy Trinity.

Comments

Post a Comment